No board exists in a vacuum; directors have lives outside the boardroom. Those lives provide knowledge and experience that is valuable to a board, and they can also present conflicts of interest for their board work. Many boards try to mitigate conflicts of interest by avoiding them altogether, but that unrealistic tactic may cause many highly skilled directors to decline board roles where they could make a real impact, provided their conflicts were managed responsibly.

Lessons on Conflict of Interest from Sustainable Development Technology Canada

When the potential for conflict of interest is embedded in the foundation of your governance, managing it carefully becomes even more crucial. Take, for example, Sustainable Development Technology Canada (SDTC), who made headlines this summer over the Auditor General’s report that found mismanagement of conflicts of interest by the Board of Directors.

The trouble gained media attention when a group of concerned whistle-blowers made allegations to Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. The Board Chair and the CEO testified to a parliamentary committee and then resigned. An independent investigation found no evidence of wrongdoing but made recommendations to improve inconsistencies and strengthen policies. Then the Minister suspended outgoing grants, and the Auditor General launched its own investigation.

SDTC was created via enabling legislation in 2001 to serve as a federally funded arm’s length foundation, operating as a not-for-profit corporation. Its mandate was to award funding for eligible projects carried on primarily in Canada to develop and demonstrate new technologies related to climate change, clean air, clean water, and clean soil to make progress toward sustainable development.

The potential for conflict of interest was embedded in its governance from the start. The Canada Foundation for Sustainable Development Technology Act required that the appointment of board directors be representative of, among other things, “persons engaged in the development and demonstration of technologies to promote sustainable development, including technologies to address issues related to climate change and the quality of air, water and soil.” This potential for conflicts of interest was further complicated because the SDTC board was not just charged with providing oversight. It also was mandated via its Act to “approve projects for funding on the basis of recommendations from the Project Review Committee and approve significant project modifications.” There were additional conflict-of-interest requirements imposed through its funding agreements, acts, and policies that applied by virtue of its board being appointed by Governor in Council.

With that level of board engagement in approval of projects, a board composed of active industry participants, and a matrix of rules and policy requirements, conflicts were destined to arise at SDTC, and their management was going to be a near impossible task for the SDTC board to handle.

So, what is a board like this to do?

Conflict avoidance may not be the best approach

Conflict of interest is not in and of itself a bad thing. In fact, avoiding conflicts entirely shouldn’t be the goal, especially if there is value in having representation in the organization of different communities, relationships, skills, or knowledge of the sector. Instead, be aware of conflicts, name them, and act to minimize their impact (and, yes, that extends to perceived conflicts of interest too). A conflict of interest – real or perceived – is not itself fatal to good governance, but they do require robust management plans to protect the integrity of the organization.

Some boards, like SDTC, have conflicts so unavoidable as to be baked right into their governance. But even when boards do not have conflict inherent to their board composition, conflicts still require close and rigorous attention. When a decision-maker has an undeclared, or unmanaged, real or perceived conflict of interest, the organization’s reputation, and the legitimacy of its decisions are undermined, as SDTC found out the hard way.

Conflict management

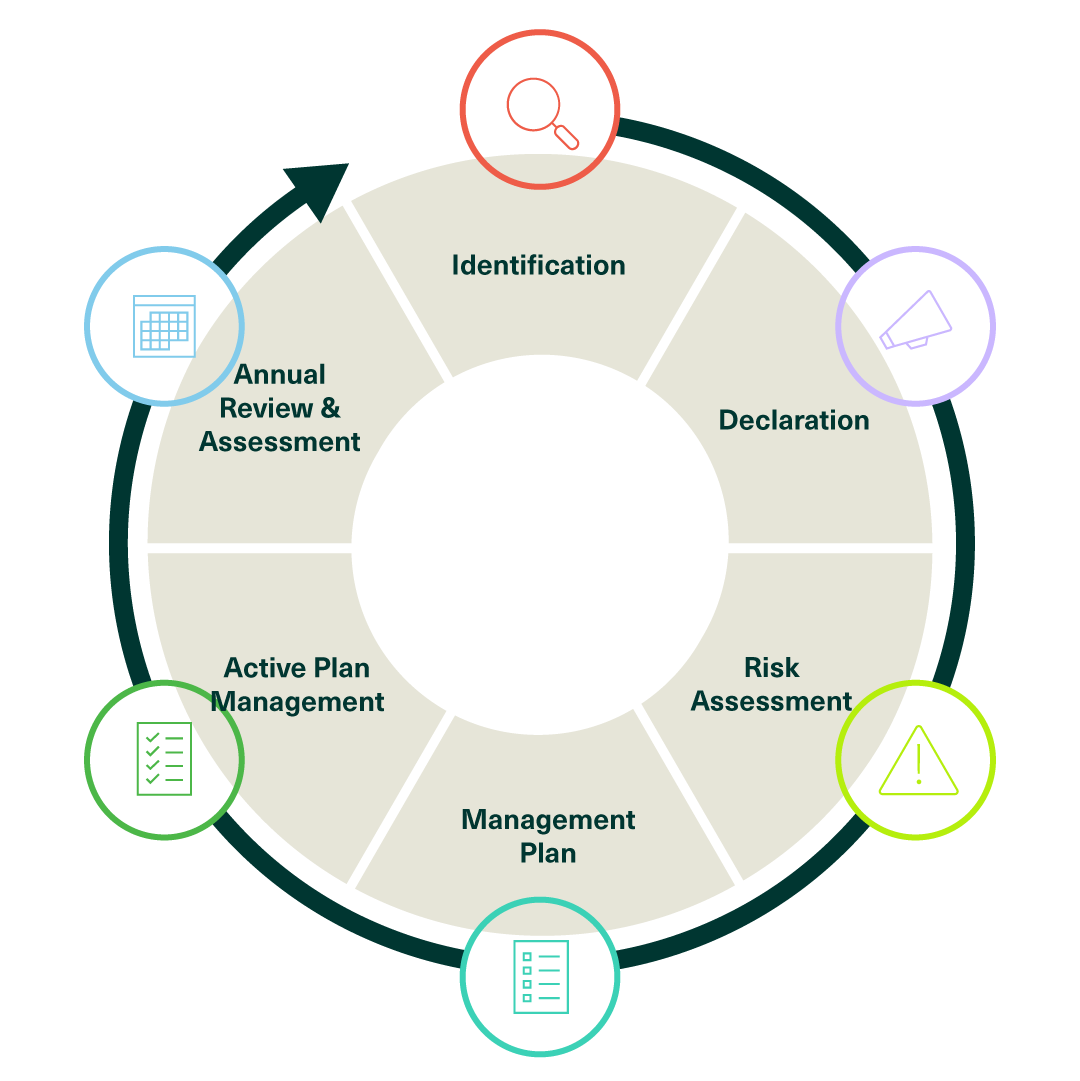

If you’re faced with a conflict of interest, many experienced directors see disclosure as the most important step in managing that conflict. But before you can make any declarations, you must first identify that a potential, perceived, or real conflict might exist. If you think it does, this is a good time to connect with your Board Chair or an ethics advisor for guidance. Declaration is almost always the next step, but in some rare cases, you may be guided to recuse yourself from a particular board duty or step down from the board without disclosing the conflict to the Board Chair or Committee Chair.

This may seem counterintuitive, but consider this example: A director serves on two boards, for organizations A and B, and is a member of the CEO hiring committee on board A. When a senior executive at organization B applies for the CEO position at organization A, the director becomes conflicted in their role on the hiring committee. Declaration of the conflict could cause harm to the senior executive of organization B and bias the hiring process. They consult an external ethics advisor, who recommends the director recuse themselves from the hiring committee without a disclosure to avoid the conflict of interest and avoid harming the applicant or the process.

When a silent recusal isn’t the right move, a declaration or disclosure is often the next step. After a declaration, the director or Committee Chair responsible for conflict-of-interest management will typically work with you to assess the risk of the conflict. The nature of the risk will determine the appropriate management plan.

Document this plan and keep it on file with the committee responsible for conflict management. Follow the policies and procedures set out in the plan, ensuring a regular cadence of review and discussion. This cycle of risk assessment and active management is repeated annually until the conflict no longer exists. One of the fatal errors for SDTC was poor record keeping on conflict disclosures and mitigations (such as directors recusing themselves from funding votes), as outlined in the Auditor General’s report.

Board members responsible for the oversight of conflict management plans must be entirely free of any conflict, which often leads to the Audit Committee playing a key leadership, management, and oversight role. Boards that adopt an active and rigorous lifecycle approach to managing conflicts, with clear documentation, over the course of the conflict’s existence until the conflict ends, will have made a wise investment in the integrity and risk management of their organization, as well as in the confidence of their stakeholders.

How to write a conflict of interest management plan

The important sections of any conflict management plan include background, details of the disclosure, management strategies, and an acknowledgement by the conflicted director.

When developing a management plan, consider the following thought starter questions:

- What is the type, nature, and scope of the conflict?

- When was the conflict declared, and to whom?

- What are the risks and how will they be mitigated?

- What is your rationale for the chosen risk mitigation and management plan?

- Who will be involved in managing this conflict and what are their roles?

- Who will sign off on this plan to add legitimacy to the process?

The best laid plans

Despite best intentions and great effort, no conflict of interest management approach can entirely prevent negative consequences from arising. Employees may leave if the conflict strongly impacts their values, stakeholders may perceive the organization negatively, and critical media stories may follow. Nevertheless, taking a robust approach to conflict management, especially when it involves the CEO or directors, will help to better equip an organization to mitigate these risks and minimize their impact should they materialize.

Conflicts of interest makes for salacious news. They often trigger an emotional response and cut to the heart of our sense of fairness. Insufficient conflict management often leaves outsiders to assume the conflict is the result of fraud, bad intentions, or exploitation for personal gain. While following your board’s current conflict of interest policies may not always be enough to avoid a scandal, a robust, documented, management process will go a longer way to preparing a more satisfactory response that addresses these stakeholder concerns. If you support an organization’s purpose enough to serve on its board, you owe it to the organization to realize your job is not finished once the conflict is declared; in reality, it has just begun.

)