Board composition is a key part of governance effectiveness. What happens when you aren’t in control of it for your Board?

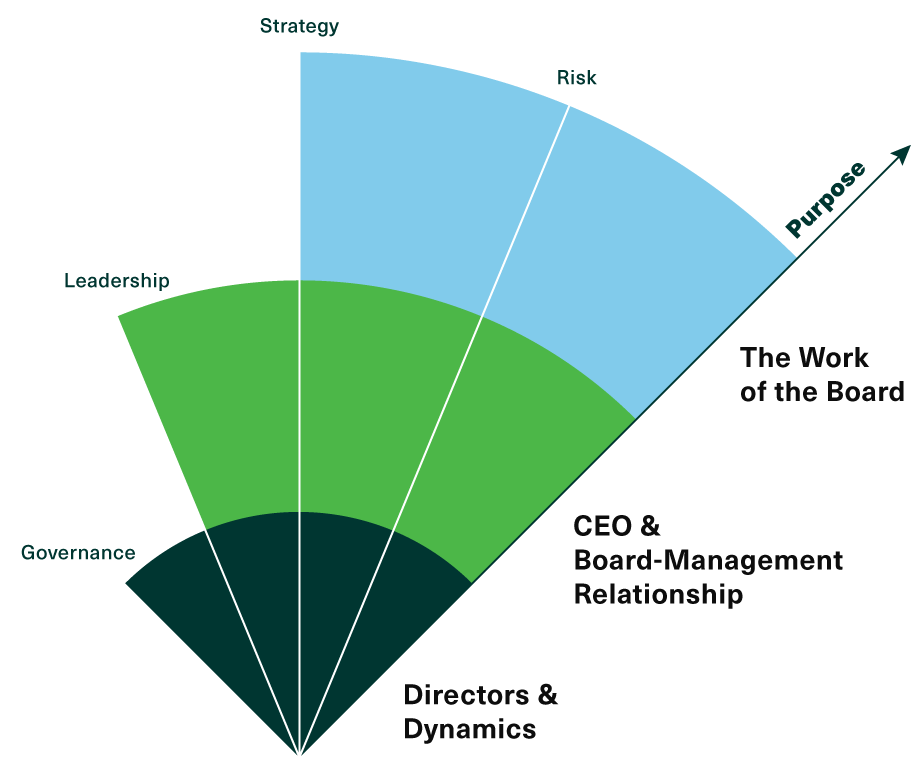

At Watson, we think about three layers that make up the world of the board. All three need to be healthy and aligned.

In the 20+ years we have been working with boards and governance, the most significant thing we have learned is that people are at the root of effective governance and board performance. The mark of an effective board is the ability to assemble the right mix of people who can provide appropriate leadership and oversight of the organization, and guide management. As an organization looks to evolve, or as context changes over time, it is essential that the board makeup evolve as necessary so that it can continue to play a strong leadership role. The layer of Directors & Dynamics is a true foundation that helps the board shape the future of the organization.

Boards must be intentional about their composition and their renewal practice if they want to be as effective as possible. Yet many boards are not fully in control of their own composition. Member-based associations, Crown corporations and agencies, higher education, regulators, cooperatives and more: many important organizations that contribute to our economies and our society are governed by boards where some or all of the directors are elected or appointed outside of the board’s direct control. Yes, it’s true that technically directors on many other boards, such as public and private company boards or not-for-profit corporations, are elected or appointed too; but usually those boards have more levers that provide greater influence over which directors are appointed; less so in the organizations we are discussing here.

Here are some real-life examples:

- A professional association’s Board is made up of members, elected by fellow members. These members care deeply about the association, are knowledgeable about professional matters, and understand member views. Due to the nature and focus of the profession, what the Board frequently lacks is the expertise from other professions, such as finance and law, or experience from people who have run other associations.

- A Crown organization is anticipating significant technological disruption, sees massive opportunities and risks around artificial intelligence, and is in the midst of changing legacy systems. It could significantly benefit from technology experience, as well as a greater diversity of lived experiences, but the Board feels it has limited influence over who will be appointed.

- A member-owned organization has grown to be very large. It has been working through a challenging change agenda due to the competitive landscape, which put its future at risk. With elections coming up, the Board sees that there are active groups of members mobilizing to elect people who will resist change.

- A university has a large Board of Governors, elected by different segments of the university community, appointed (by government or others), or participate by virtue of their office. As pressures on universities multiply, the Board must navigate complex issues, under a spotlight – yet governors feel powerless to ensure they have all of the right skills and experience around the table. And, relatedly, not all governors feel that what they do bring to the table is fully valued by peers, depending on the mechanism by which they were appointed.

- An airport authority’s Board has members appointed by a several different bodies: three levels of government (federal, provincial and multiple municipalities) as well as a range of other organizations in the community and local economy. Directors worry about gaps in expertise and diversity, as well as how to manage Board leadership succession (Chair and Committee Chair), given the limited control over appointments, the variety of experience and levels of engagement around the table, and the steep learning curve around the complex business of being an airport authority.

- A regulator has both elected and appointed members on its Council. A significant challenge is that few come to the table with experience and knowledge of governance, alongside understanding of the regulated sector and its complexity. Each group brings specific knowledge, but little bridges them together.

Let’s pause to talk about why these circumstances exist. It is easy to focus on the challenges and concerns for boards when they feel out of control over their composition. However, in general, in the organizations we are referring to, these election or appointment practices are intended to ensure a board does not become insular and self-serving, or lose its connection to the needs and expectations of its members, owners, shareholders or rights-holders. These election and appointment practices were generally designed, intentionally, to ensure the organization retains a sort of integrity of purpose over the long run.

The question becomes how a board can respect the purpose these arrangements were designed for, and the roles and rights of electing/appointing bodies, yet also help shape its composition? Many boards feel powerless; they are not. At Watson, we have helped boards achieve significant progress. Nothing is guaranteed; but if we start from a place of all players wanting the organization to thrive and be sustainable for the long-term, then we can look at opportunities to guide and shape elections and appointments.

This work should be done transparently and with positive intention; it is not about maneuvering or manipulating. It is about helping those who do control the outcome understand why composition is important, what the Board needs now, and how they can help.

Real-world tested approaches proven to make a difference.

The types of strategies we’ve deployed with success include:

1. Developing a skills, experience, diversity and competency matrix that looks at what is needed on the board, based on purpose, context, values and strategy. This includes a time dimension, looking at director succession. Identifying a small number of priorities to focus short-term efforts (next election/appointment cycle) and long-term efforts (addressing any systemic barriers/challenges). This matrix can then be shared with the membership, nominating or appointing bodies. It communicates what is needed rather than prescribing the specific person which better respects the nominating, election and appointment processes.

2. Providing clear and compelling communications and business cases to the electing or appointing bodies, spelling out what kind of director talent is needed and why, from the perspective of impact and risk (including what’s in it for them). This may include written communications, key meetings with influential parties, and town halls. Again, transparency is important here; this is about positive influence for shared good, not political maneuvering. Like the matrix, this is an approach that communicates what is needed rather than prescribing the specific person, which better respects the nominating, election and appointment processes.

3. Searching for talent with specific skills, experience and diversity within the membership, in an active executive search-type process; deliberately seeking out candidates within the membership rather than waiting purely for self-selection. Sometimes the best people need to be asked to understand the need and the opportunity for impact!

4. Creating a pipeline that helps expose future directors to governance matters and the workings of the organization, so that they become prepared to be well-rounded governors in the future. This can include committee work, development, mentoring, etc. This can be especially helpful in addressing gaps in governance knowledge, and increasing board diversity over time.

5. Having a nominations and candidate preparation process that helps people understand the true nature of what they are signing up for (e.g. a duty to the organization and all its stakeholders, not a focus on a flashpoint issue they may wish to address; a focus on governance, not directing operations; requirements and responsibilities of directorship, including everything from time commitment and preparation to confidentiality). Candidates can also be walked through the skills, experience and diversity priorities to understand what they are, and self-assess against those before confirming a desire to run.

6. Recommending prospective directors for election who meet key needs and asking (respectfully and with humility) for their appointment; again here, explaining the “why” in a way that makes sense to the electing or appointing bodies, based on what’s important to them and the shared interests of all.

Strong and effective governance is a shared priority, and boards often have an insider perspective on what is needed here and now. All of the above is about making those needs clear to those who affect the outcome and believing that reasonable people, armed with the best possible information, will make good decisions. Sometimes there are other dynamics at play, related to trust, organizational performance or other factors; when that’s the case, we need to tackle those things too.

)

)