In the world of CEO succession planning, timing is everything. Unless your board is clairvoyant, pinpointing the perfect moment to change CEOs is almost impossible, but there are practices that can get you close. It all starts with a shift in board mindset from the wait-and-see to the optimal timing approach.

Determining the optimal CEO transition time is the board’s most important and most difficult job. And the sad fact is, most boards don’t think about it enough, and almost completely ignore it in the early days of CEO tenure or when performance is strong. Too many boards wait for the CEO to make the first move and declare a retirement date, and even when given considerable lead-time, boards unconsciously fail to put the best interests of the organization ahead of the CEO’s.

Consider the case of the CEO who respectfully gives her board two and a half years retirement notice. The board takes that as their order ticket and gets to work. There is plenty of time to determine the skills needed, hire a search firm, develop internal candidates and hone their interviewing skills. But what makes two and a half years the optimal time? Boards need to stop blindly accepting the CEO’s timeline and start asking, “what is the best time for the organization?”

The Optimal Time for CEO Transition

Early in their tenure, new CEOs come up the learning curve and perform well for a few years or maybe many years but eventually, performance falters, if only because the CEO is 100 years old.

The optimal time to change out the CEO is just before the decline. But what are the chances that your board will achieve this optimal timing? Highly unlikely. The board’s job is to constantly look into the future, predict the arc of the curve and tackle transition before performance drops. There are situations when the CEO leaves while performance is still strong, as in the case of unforeseen illness, retirement or in pursuit of another opportunity. The board has less control in these scenarios. But in many cases, strong organizational performance lulls boards into a state of succession planning complacency and early warning signs are dismissed. As one director reflected after a later-than optimal transition, “yes, performance slipped a little and a couple of directors had some criticisms, but with his long track record, the board remained confident that he was doing a good job.”

It is not unusual for boards to avoid the touchy topic of transition until poor financial results or a failed initiative jolt them out of complacency. Too often it takes them a long time to see the decline in the CEO’s performance, reach consensus to terminate the CEO and then orchestrate the departure. The optimal timing approach requires your board take a different tack.

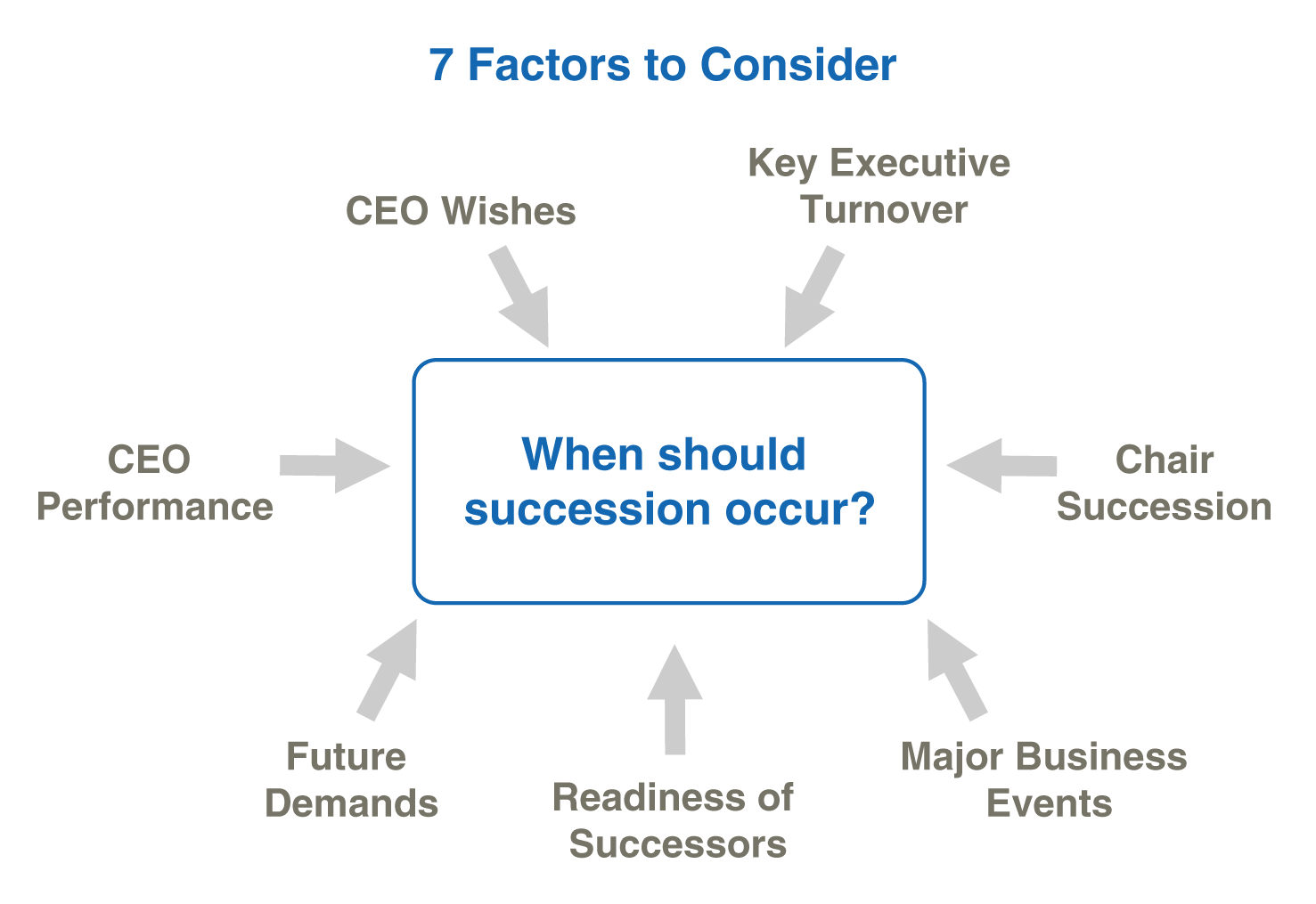

Seven Factors Effecting CEO Succession Timing

Your board may never achieve optimal timing, but it is your job to get as close to optimal as possible. Consider these seven factors when your board thinks about the timing of CEO succession.

Major factors that get you in the ball park

1. CEO Wishes When does the CEO plan to leave? The CEO may be reluctant to share this too far in advance for fear of being labeled checked out and / or lacking in commitment. They may also be afraid of the permanence of the decision – What if I change my mind? What if this speeds up the process? Ask the CEO what they have in mind, even if it is a range of possibilities. For a CEO approaching retirement, financial matters may be a driver. Be cognizant of the CEO’s Personal Financial Calculator, the ongoing tally of the value of their pension, incentive plans and vesting of shares or options that might shape their preferred retirement date. For younger CEOs, understand that they might want to have one more gig or other challenges in their career. Do you really want a 48-year old CEO to stay in the same role for another 15 years?

2. CEO Performance Invest in a robust CEO performance evaluation. Ensure the full board is engaged in the process and has the opportunity to provide feedback. Examine how well the CEO is doing separate from the organization’s performance. Understand the strengths and the weaknesses of the CEO and weigh carefully if this adds up to the right leader at this time.

3. Future Demands In concert with strategy development, assess the CEO’s mandate for the future. How is the role changing? What will the CEO need to do in the future? How might that differ from the past?

Minor factors that may tweak the timing a little sooner or a little later

4. Major Business Event Adjust CEO transition timing in light of major events within the organization or the industry; for example, an upcoming IPO, completion of a massive capital project or completion of a major negotiation.

5. Chair Succession Stagger Chair and CEO turnover so both roles don’t turn over within 18 months of each other. Allow time for the incumbent to learn from the outgoing party and secure organizational continuity.

6. Key Executive Turnover Identify potential turnover of key executives and either accelerate or slowdown the CEO or the executive’s transition timing. Key roles may vary based on industry, for example a COO in a mining company or Chief Investment Officer in an asset management company. Pay particular attention to the role of CFO.

7. Readiness of Successors If your board has identified potential internal successors, factor in the sweet spot for transition. Be prepared to delay or accelerate transition. For example, if a high potential candidate needs one more year to be ready, consider asking the CEO to stay on for a year, or, in the case of a potential candidate flight risk, move up the transition timing.

At least once a year, have an explicit discussion with your board about the optimal succession timing, without the CEO present. This will get your board started on the right foot and make it more likely to achieve the best leadership for today and for the future.

Hey WATSON, if boards know they should plan for transition, why is there so much reluctance to engage in the succession planning process?

The simplest answer: it is darn hard work complicated by personal relationships. Loyalty clouds perspective. Too often we hear boards lament, “we owe it to him” or “who are we to take her out of the job?” For many boards, avoidance is easier than awkwardness. In the absence of annual discussions, boards fear giving the wrong impression to the CEO when they start talking about succession. “If we are talking about it, the CEO might think a change must be imminent and it’s time to call the search firm”. This is a myth. Regular ongoing dialogue is a sign of healthy succession planning, not a failure in leadership.

Have a governance question?

The optimal timing model is neither a prediction nor a locked-in plan. It is a powerful focal point for planning. It influences the list of potential candidates and their development plans. It changes the board’s work plan. It changes what gets communicated to whom. Over time you may change the focal point, but it will set the pace and keep the board on track.

)

)

)